*

*

Képzőművészeti Egyetem

2010 végzés

Kovács Attila mester

Hogyan kerültél a képzőművészeti pályára?

Gyerekként sokat rajzoltam, mivel kedves, de problémás gyerek voltam, és a rajzasztalnál nem volt velem baj, törvényszerűen egy idő után mindig ott kötöttem ki. Az egész családomról elmondható, hogy átjárja valamiféle transzcendens igény, így nem volt meglepő, amikor anyám érezni vélte a jövőm. Miatta nagyon korán, komoly képzőművészeti képzést kaptam. Celldömölk mellől vagyok, élt ott a városban egy festő, egy vidéki mester, ő tanított meg rajzolni.

Utána a szombathelyi Kisképzőn átlagon felüli művészeti oktatást kaptam, később pedig a Képzőművészeti Egyetemen folytattam a szintén átlagon felüli Kovács Attila mesternél, akivel nagyon szoros baráti kapcsolatom lett. Bár minden olyan gördülékenynek tűnhet, azért volt pár évnyi rossz döntésem, mert a gyors siker reményében elkezdtem képregényekkel foglalkozni, és elvitt egy populáris irányba, ami mint kiderült, nem nekem való. Az ezzel elvesztegetett 2-3 évet később vissza kellett dolgoznom.

Te, hogy találtál vissza a populáris irányból?

Idővel rájöttem, hogy ahhoz, hogy szeressék a képregényeimet, változtatnom kell magamon. Meg kell felelni a populáris ízlésnek és beláttam, hogy ha magamhoz mérten a legjobb képregényt csinálom meg, akkor önmagamtól kell búcsút vennem. Mivel alapvetően nonkonformista személyiség vagyok, ez nem működhetett. A képregény egy nagyon jó műfaj, de nekem nem felelt meg. Bár továbbra is szeretem, a populáris dolgokkal sincs semmi bajom és fogyasztom is, de nem csinálnám már. Viszont a magyar képregény kultúrában sikerült egy negatív példát létrehoznom, azaz, hogy hogy ne csináljunk artisztikus képregényt.

Hogy alakult az érdeklődési köröd?

Komoly katolikus neveltetést kaptam, de ennek ellenére, nem voltam vallásos soha, viszont mindig érdekeltek a szakrális történetek, jelképek. Érdekes módon az élethez fűződő legelementálisabb vitalitást a legnyugodtabb szakrális tárgyakban és festményekben találtam meg. Számomra egy szakrális kép valami mélyen emberit jelképez. Ha ránézel egy ilyen képre, akkor látsz egy figurát, ami egy transzcendens idea, egy nyugodt emberi allegória, ami az emberi természet valamelyik pozitív oldalát mutatja. Valójában nagyon egysíkú abszolútumok, amik megerősítik a nézőben a saját maga erényeit, statikus állandók az ember másodpercenkénti jó-rossz változásaival szemben.

Ugyanakkor úgy néztem ezekre a tárgyakra, hogy sose láttam mögöttük a vallást, csak a művész nívóját, emberileg és művészileg. Jóllehet, fiatalabb koromban ezeket a szakrális alkotásokat nagy tételben fogyasztottam először könyvekből aztán főként az internetről, gyakran vallási ideológiákról nem tudva. Már gimisként közlekedtem a különböző vallások, különböző alkotásai között úgy, hogy magáról a vallásokról nem vettem tudomást. Csak, mint műtárgy érdekelt és az általános jelentéstartalom.

Én a munkáimban pozitív emberi ideákat hozok fel a közös kultúrtörténetünkből. Úgy határozom meg magamat, hogy nem csinálok szekuláris festészetet, de vallási festészetet se, valahol a kettő közötti emberi dolgokkal szeretnék foglalkozni, transzcendens, nem egyéni sorsok, hanem egyszerűen egy általános emberi nívót szeretnék mutatni. Ezeket az allegóriákat Etalonok-nak (2015-től) nevezem, a művészetemet pedig, mivel látok a művészettörténetben, de kifejezetten a szakrális művészetben folyton ismétlődő rendszereket, ’etalonformel’-nek (etalon formula-nak)(2018-tól)(előkép: Aby Warburg: ’pathosformel’) hívom.

Szerintem nagyon elszakadt az ember önamagától, az érzelmi és transzcendens vonalától, és az így kialakult értékválság remekül megterít egy olyan művészetnek, mint amit én képviselek.

Hogy jutottál az aktuális munkáidig?

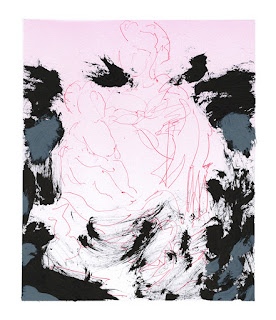

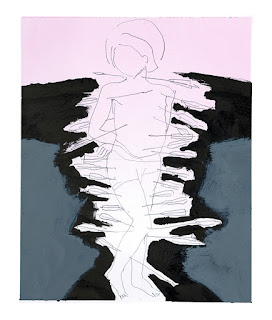

2014-ben, amikor az első komolyabb kiállításom volt (NextArt Galéria, Bp.), akkor még fehér figurális képeket festettem görög mitológiai vonalon. A görög hagyományban leginkább a Hermafrodita, mint figura tetszett meg, aki nem férfi és nem nő, hanem egy azelőtti állapot, közös, partícionálatlan ősi egység. Ezek általában fehér képek voltak pár centis fekete tus bevágásokkal. Később a képeimen a tusfelületek egyre szélesedtek és eljutott oda, hogy a teljesen világos fehér képből a figurákat kivágja egy homogén fekete tusfelület. Ez már egy másik sorozat az ’Elzárt Kert’ lett. Később a tusfelületre is ráfestettem és akkor jöttek létre a mostani képeim, valamint mindezzel párhuzamosan egy absztrakt expresszionista irányt is vittem. Mindegyik egy fejlődési szakasz része volt és tulajdonképpen már egyben kezelem mind a hármat, mint Etalon sorozat.

Miért mentél el egy absztrakt irányba?

Egyes munkáim azért absztrahálódnak, mert ahogy minél jobban meg tudtam fogalmazni tartalmilag mi érdekel, úgy kezdett létrejönni bennem egy fogalmi igény. Ezt úgy határoztam meg, hogy nem akarok konkrét figurákat festeni, csak a figurák lényegi részét. Úgy vélem, a fogalmi igény a festészetben az absztrakció. Egyébként nagyon szimpatikus nekem a Twombly-féle vonal az ösztönös gyermeki képalkotás is. A mesterem fiával, Zozóval (6) fogok nyáron festegetni és már előre látom, hogy sokat fogok tőle tanulni. Kíváncsi vagyok, hogy mit tudunk majd ebből ketten kihozni. Az, hogy elmentem absztrakt irányba is, sok kérdést hozott és ezeket meg kell válaszolni formailag. Talán ez a gyermeki tisztaság fogja megoldani.

Technika?

Az egész életemet végig követte a tus. Valamilyen oknál fogva mindig is vonzódtam hozzá. Mondhatnám, azért mert félig laoszi származású vagyok, de mivel ott nincs tus használat, billegne ez az állítás. Ehhez használok még akrilt. Van, amikor airbrush-al viszem fel a festéket, valamikor ecsettel. Absztrakt munkáimnál az airbrush-t csak enyhe színfelület képzésére használom, mint a transzcendens fényt. Egyébként ez az ikonográfiában általában arany színű, de itt most nekem rózsaszín lett. Azt, hogy miért rózsaszín, még nem tudom. A rózsaszínnek a katolikus hagyományokban ugyan van értelme, de engem ez nem érdekelt, nem így jutottam hozzá.

Általában nem tapasztalati úton fejlődök. Az intuícióm nagyon jók és utána mindig hozza az élet a magyarázatot. Ez kivétel nélkül így történik, olykor évtizedekkel előre. Megtanultam az előérzeteimre hallgatni és ezért olyan eszközökhöz, tartalmakhoz vagy formai változatokhoz nyúlok, amiket nem biztos, hogy akkor, abban a pillanatban meg tudok magyarázni, egyszerűen csak egy érzet.

Jövőbeli tervek? Külföldi tervek?

Fizikailag szeretnék mindenképp itthon maradni, mert itt minden rovar tudja, mekkorára nőhet ami még nem pofátlanság, és ez nekem nagyon fontos szempont, illetve a megszokott növényekről sem tudnék lemondani. Egyébként külfölddel kapcsolatban hosszabb-rövidebb tartózkodásokban és állandó szakmai jelenlétben gondolkodom (Eddigi megjelenések: SCOPE Art Show, Miami, AAL-Arte Al Limite, Brasil).

*

Hungría | Pintura | Bardon Barnabás

Without Gods, there would be no history

Barnabas Bardon reminds us of Greek mythology, between reason and urge, and also invites us to reflect upon our concepts of humanity, beauty, nature, and neutrality.

Transparency becomes consistent through the look of the hermaphrodite beings that inhabit his paintings. Soft, weak layers, with small, black, strong, groundbreaking spaces. Each being portrayed next to an animal, an object, or a mountainous landscape. Barnabas Bardon’s artwork captivates through its underlying messages, through the intention it supposes, the imagination it insights, and the memories of Greek mythology evoked.

Bardon lived the first twelve years of his life in a small town in Hungary. Surrounded by animals, nature, and sunshine, where there was nothing that could endear him to art, where there were no artistic representations. Nothing evident or direct, like galleries or museums: only a church that contained religious objects and statues he could touch, and that produced a powerful effect over the artist. It is during these experiences that his creations move closer towards religion, and we are reminded of classical European history, through his hermaphrodite beings, in a figurative form.

The artist considers Nietzche’s philosophy a direct influence, and also “his Apollonian and Dionysian personalities. Whilst Apollo represents reason and rationality, Dionysius symbolizes irrationality, chaos and euphoria,” he explains. The artist was also marked by Fellini’s move Satyricon that deals with the hermaphrodite theme in many levels.

Innocence, silence, and permanence

“I consider hermaphrodites as the most beautiful and pure beings of Greek mythology, since they are not a man or a woman, but just one. They represent common human beings in a perfect way: no gender or sexuality, just a ‘human being’ in his pure state,” Bardon explains after being asked why his characters are portrayed as hermaphrodites, androgynous or sexless. But, as he explains, this similarity is deep, clear, and clings to the beginning of European histories to the fact that “some hermaphrodites reveal a positive human ideal that is lovable and can be considered normal. This is the case of Hermes, messenger of the Gods, and Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty; Hermes is not evil or ugly, but a genetic form in mythology.”

It is due to the creator of the lyre, an instrument constructed by stretching ropes over a tortoise’s shell, that the artist obtains the meaning of his artwork. Good and evil come together, and debate over the paleness of color and the strength of that dark stain present in each one of his pieces; a confrontation between the pure, peaceful aspects of humanity, and its negative and aggressive ones; between Apollonian and Dionysian with neutrality in the middle. A being that is not naturally born good or evil, as contractualists debated; a being that appeared before our existence, that meant perfection to Plato, since it represented both sides of humanity. That being that tries, in present times, to be accepted and adapt to a dualism that goes beyond unity.

Bardon’s artwork strongly fights against antagonism; it is strong, it causes an impact and incites a deep reflection about reason and passion, between what we own and what we desire. Between our unconscious mind that craves to kill and soak with explosive-expulsive heat, whilst our mind settles us down, calms and stops us. “My goal is to represent silence, peace and purity by emphasizing the Apollonian side of human personality. Whereas black tones on the surface of paintings represent humanity, negativity, the Dionysian side. However, this is not in harmony with the rest of the image, since there is no Apollo without Dionysus,” the artist says.

Between these dualities we encounter the question about beauty and idealism, concepts that were addressed from Sophists to modern times and that has captivated human beings due to the versatility of its definitions, as well as the sublime experiences associated to them. But, where do we find beauty? How do we get close to it? Is this something related to senses, or does it imply a superior knowledge? Endless doubts seem to be answered in Bardon’s work through an unparalleled simplicity of tone that becomes deep due to the contents it evokes. It is both a pleasant and a provocative sight, and also a way of moving us closer to the idea of superior good through the underlying symbolism of bay crowns, reminders of classical times. In those animals that represent a return to natural, his childhood, ourselves and our origin; in the frontal look of a neutral face, not smiling, but making small gestures that speak about subtle movement; with a landscape repeated during his first twelve years of existence and that breaks away from large cities, in which nature is forgotten and becomes huge blocks of glass and cement. And right there, a small part of the mountains moves us, makes us wonder if it is erroneous and turns our glance to dark blackness that moves us away from the idea of beauty, or makes it become alive. There is no way of creating or getting to know a concept without its opposition, there is no possibility for Apollonian without Dionysian.

by Elisa Massardo (AAL – Arte Al Limite)

*

Sin dioses no habría historia

Entre la razón y las pulsiones, Barnabás Bardón nos recuerda la mitología griega, y a la vez que nos invita a reflexionar sobre los conceptos de belleza, del ser humano, de la neutralidad y la naturaleza.

La transparencia se hace consistente a través de la mirada de los seres hermafroditas de sus pinturas. Capas suaves, débiles, con pequeños espacios negros, fuertes, rupturistas. Cada ser con un animal, un objeto y un paisaje montañoso. Las obras de Barnabás Bardon cautivan por sus mensajes subliminales, por la intención que suponemos, por la imaginación que convoca y por los recuerdos de la mitología griega.

Bardón vivió los primeros 12 años de su vida en un pequeño pueblo de Hungría. Rodeado de animales, naturaleza y sol, donde no había nada que representase o pudiera acercarlo al arte. Nada evidente ni directo como galerías o museos, solo una iglesia con objetos religiosos y estatuas que podía tocar y las cuales causaron un poderoso efecto sobre el artista. Es desde estas experiencias que sus creaciones se acercan a la religión y recuerdan con un estilo figurativo la historia clásica europea a través de seres hermafroditas.

Pero entre sus influencias directas el artista también destaca la filosofía nietzscheana y “sus personalidades apolíneas y dionisiacas. Con Apolo representando lo racional y la razón, mientras que Dionisio simboliza lo irracional, lo caótico y la persona eufórica”, explica el artista que igualmente quedó marcado por la película Satyricon de Fellini, la cual se conecta con el tópico del hermafrodismo en muchos niveles.

Inocencia, permanencia y silencio

“Creo que los hermafroditas son los seres más hermosos y puros de la mitología griega, porque no son ni hombre ni mujer, es solo uno. Es perfecto para demostrar al ser humano común y corriente que quiero representar: sin género o sexualidad, solo un ‘ser humano’ en estado puro”, explica Bardón al ser preguntado sobre sus personajes que parecieran ser hermafroditas, andróginos o asexuados, pero tal como él explica, la identificación es clara, profunda y se arraiga en el principio de las historias europeas, en el hecho de que “los hermafroditas demuestran un ideal humano positivo que se puede amar y orientar o considerarse como normal. Este es el caso de Hermes, mensajero de los dioses, y de Afrodita, diosa del amor y la belleza; Hermes no es un ser feo o malévolo, sino que es la forma genética en la mitología”, explica el artista.

Y es gracias al creador de la lira, hecha tensando cuerdas sobre el caparazón de una tortuga, que el artista adquiere el fundamento para su obra. El bien y el mal se conjuga y debate entre la palidez del color y la fuerza de esa mancha oscura en cada uno de sus trabajos, las cuales son una especie de lucha entre la paz y la pureza con lo negativo y agresivo de la humanidad; entre lo apolíneo y lo dionisiaco, y en el centro lo neutro. El ser que no nace bueno ni malo por naturaleza según los contractualitas debatían, el ser que aparece anterior a nosotros mismos, que para Platón era perfecto por ser ambos a la vez; el ser que en la actualidad trata de ser aceptado/adaptado a un mundo que se ha acostumbrado a la dualidad más allá de la unidad.

En esta lucha de antagónicos la obra de Bardón es fuerte, impacta y genera una profunda reflexión entre las pasiones y la razón; entre lo que debemos y lo que queremos; entre nuestro inconsciente que desea matar y colmar con un acaloramiento expulsivo/explosivo, a la vez que nuestra mente nos apacigua, calma y detiene. “Mi meta es representar el silencio, la paz y la pureza por medio del énfasis del lado apolíneo de la personalidad del ser humano. Donde los tonos negros en la superficie de las pinturas representan la humanidad, lo negativo, el lado dionisiaco. Sin embargo, esto se encuentra en armonía con el resto de la imagen porque no puedes tener a Apolo sin el caos de Dionisio”, cuenta el artista.

Entre estas dualidades se encuentra la pregunta sobre el idealismo y la belleza, conceptos que fueron abordados desde los sofistas en adelante y que ha cautivado al ser humano tanto por su versatilidad de definiciones como por las experiencias sublimes que a ello se asocian. Pero ¿dónde encontrar la belleza? ¿Cómo acercarnos a ella? ¿Es esto algo adepto a los sentidos o implica un conocimiento superior? Un sinfín de dudas pareciera responderse en la obra de Bardón a través de una sencillez inigualable en la tonalidad, que a su vez se hace compleja en la profundidad de la obra por los contenidos que aboca. Y siendo una obra agradable a la retina y provocativa para los sentidos, es también una forma de acercarnos a esa idea de bien superior por el simbolismo implícito en las coronas de laureles, recordatorio de la época clásica; en esos animales que son un retorno hacia lo natural, a su infancia, a nosotros y nuestro origen; en la mirada frontal de un rostro neutro, sin sonrisa, pero con pequeños gestos que hablan de un sutil movimiento; con un paisaje que vio durante sus primeros doce años de vida y que se alejan de las grandes urbes actuales en las que la naturaleza se olvida convirtiéndose en grandes bloques de cemento y vidrio. Y justo ahí, una pequeña parte de las montañas nos conmueve, nos hace pensar en un error y desvía la mirada para centrarse en el negro oscuro que nos aleja de la idea de la belleza o que la hace existir. No hay forma de crear o conocer un concepto sin que tenga un opuesto, no hay forma de que exista lo apolíneo sin lo dionisiaco.

by Elisa Massardo (AAL – Arte Al Limite)

*

Barnabás Bardon: Etalon man series – ” Enclosed garden “

The Enclosed garden, also known as Hortus conclusus, is the title of Barnabás Bardon’s latest exhibition. The garden, both as a conceptual and physical phenomenon, spreads through our cultural history with thousands of different explanations to it. Yet, Bardon interprets it as a symbol that expands from the Middle Ages, through the Renaissance, into the Baroque. In this view, the garden is the attribute to the place where humans return to themselves, for contemplation.

On Bardon’s paintings we see some secret gardens, a transcendental environment that the artist’s allegories inhabit. However, in this private mythology we can’t define the figures in a racional manner, but rather as human emblems, idols of the ancient virtues. The stage, where these allegorical beings display tiny momentums, is the venue of a mythical event; the enclosed garden itself.

The „Etalon man” pictures are in parallel to Bardon’s earlier, „Hermaphrodite” series, only this time it’s another character appearing. The style, utilised by the artist and influenced by the Baroque, indicates a certain sacredness; an aim at capturing some kind of a heavenly miracle. Similarly to the classic androgynous god, the „ Etalon man” illustrates a pure, taintless personality as well. A sort of fundament to mankind, that is worth adapting to and is still clear of all the worldly impurities …

*

Bardon Barnabás : Etalon ember sorozat – " Elzárt kert ”

Az Elzárt kert, vagyis Hortus conclusus, Bardon Barnabás legújabb kiállításának címe. A kert, mint fogalmi és fizikai jelenség végigvonul kultúrtörténetünkön, különböző írások ezerféleképpen magyarázzák, Bardon azonban a középkortól a reneszánszon át a barokkig terjedő szimbólumként értelmezi. Ebben a felfogásban a kert az ember önmagához való visszatérésének, meditációs helyének a jelképe.

Bardon képein egy-egy titkos kertet látunk, egy transzcendentális környezetet, ahol a művész allegóriái élnek. Ebben a magánmitológiában a figurák nem racionális módon értelmezendőek, sokkal inkább emberi jelképekként, az ősi alaperények bálványaiként. E színpad, ahol az allegórikus alakok apró mozzanatokat jelenítenek meg, egy mítikus esemény helyszíne, maga az elzárt kert.

Az " Etalon ember " képek jelentésükben párhuzamosak Bardon korábbi " Hermaphrodita " sorozatával, azonban itt egy másik karakter jelenik meg. A barokk ihletésű stílus melyet a művész használ, egyfajta szakralitást jelez, valami égi tünemény megragadásának elérését.

Akár az antik androgün isten, az " Etalon ember " is egy tiszta, romlatlan személyiséget illusztrál. Az emberiségnek egy olyan alapja, amelyhez érdemes igazodni, amely még szabad minden világi szennyeződéstől ...

Barnabás Bardon „Apollon Series – Hermaphrodite”

Encolpius and Ascyltos visit the Demi God Hermaphrodite residing in the cave of the old Celes temple. The place is full of worm face pilgrims, ill from abundance, crippled by selfish wars, offering their worldly treasures to rid themselves of their anguish through magical healing. In his Satyricon, Fellini introduced a dying infant deity. The beauty of the child of Hermes and Aphrodite creates a vacuum in the iron world, and as the wrists and knees of Margarita swell in excruciating pain from the kisses of thousands of seekers, so is Fellini’s Hermaphrodite dying from the millions touching him. His fate is inevitable, the infant will die, as they rip him apart driven by the insanity of need. However this fate (as typical of Greek Deities) is not final, the past and the present swim apart in the archaic timelessness. Birth, death, and life stretch on each character.

Among the stage of my works, the first figure is Hermaphrodite, the eternal purity. Surrounded by transcendence and the first voice, silence. Classicist painting allows for the human created heavenly object be exactly approachable, but the symbolism behind the idol is only presumed, urges to synthesize the content, and as my religion, Reminds

*

Bardon Barnabás : Apollon series – Hermaphrodita

Bardon Barnabás Apollón-sorozata művészettörténeti korszakok interpretálásával, átvett képi toposzokkal és elanyagtalanított érzékiség segítségével sajátságos, individuális mitológiát hoz létre.

A festmények a nietzschei két alapprincípium, az apollóni és a dionüszoszi lélek kettősségét példázzák, ahol az alkotó apollóni formákba rendezi a zabolátlant, az ösztönöst.

A Hermaphrodita-képek az elvont, absztrakt formaelemek, valamint a kulturális kontextusok és történelmi tradíciók egy képen való megjelenítésével szabad asszociációs mezőt hoznak létre, transzcendens allegóriát idéznek meg. Ez a különös ’harmonikus eklektika’ legalább annyira létélményen alapuló szubjektív esztétikai önfelszabadítás, mint általánosító, civilizációs tükörkép.

Képeim színpadán az első alak Hermaphrodita. Az örök tisztaság. Övezi a transzcendencia és az első hang, a csend. A klasszicista képalkotás megengedi, hogy az ember alkotta ’istentárgy’ egzakt módon megközelíthetővé váljon, de a bálvány mögötti szimbolizmus csak sejtet, mitizál, a tartalom szintézisre késztet, és mint a hitvallásom, Emlékeztet.